- Have Any Question?

- 443-983-5232

- info@moosepondassociation.org

Research Reveals Algae in Moose Pond

- Home

- Research Reveals Algae in Moose Pond

Project Details

- Category : Research

- Date : Fall 2013

- Status : N/A

- Tags : Algae, Research, History

- Live demo : None

- 15 Oct 2013

- Research

Research Reveals Algae in Moose Pond

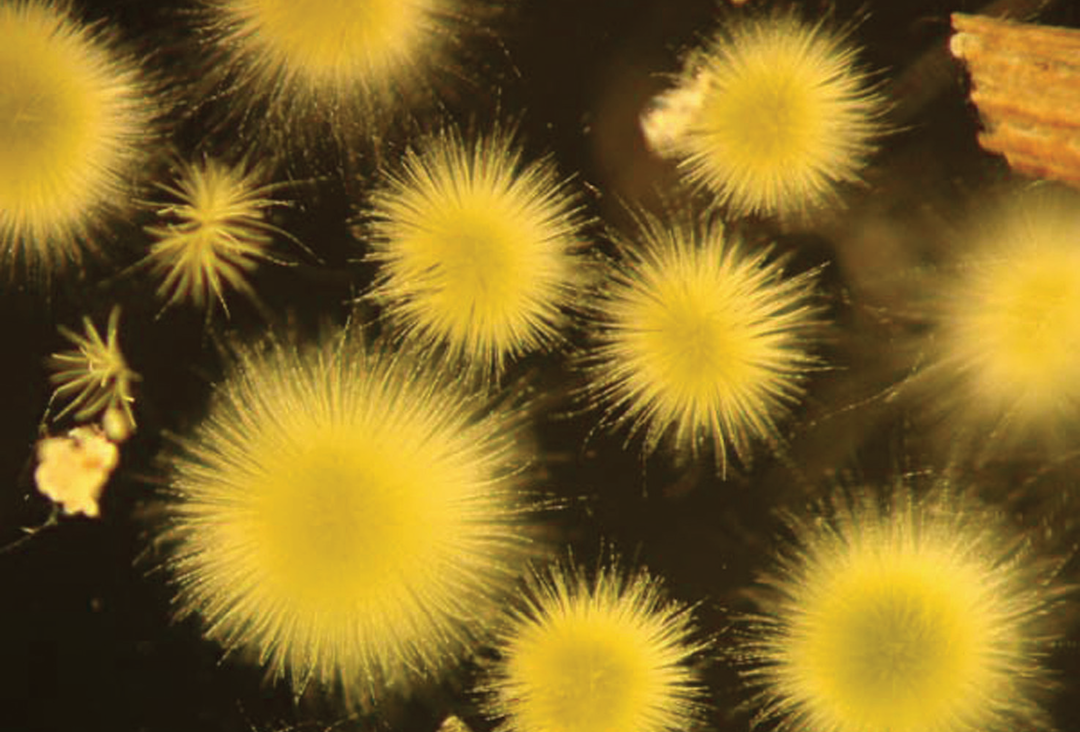

Goeoticia echinulata, (GLEE-oh-TRICK-ee-ah e-KIN-yoo-LAIT-a) or simply “Gloeo,” was discovered in Moose Pond this summer when the Lakes Environmental Association (LEA) stepped up its water testing parameters. Gloeo looks like small, fuzzy, yellow-green floating dots.

Amanda Pratt, who earned her undergraduate degree in Environmental Science from the University of Southern Maine and a Masters degree in River Basin Management from the University of Stirling in Scotland, was hired by LEA to conduct research this past summer. Her project was to implement the testing of three new parameters: temperature, Gloeo and core sediment for iron and aluminum. The Moose Pond Association teamed up with LEA to have Amanda conduct these additional tests in the middle basin. They also took sediment cores from the upper and lower basins.

For four decades, LEA has been monitoring the water quality of Moose Pond, which has long been considered one of the cleanest lakes in the region. Usually, algal blooms are associated with bad water quality due to high phosphorus in the water column. Gloeo is a bit different from most other algae in that it grows on sediments. When phosphorus increases, Gloeo feed on it and grow. Though it doesn’t necessarily release phosphorus back into the water, it has the capacity to do this.

Concern exists because Gloeo is a cyanobacterium that contains low levels of toxins. It can affect the liver of livestock, dogs and other small animals that drink water. It won’t affect your skin and you’d have to consume a lot of water for it to affect you. “It’s capable of producing toxins,” says Pratt, “but that doesn’t mean it does all the time. One reason we’re concerned about it is that traditionally we haven’t seen huge numbers of Gloeo in New England lakes. Decades ago, when algal surveys were conducted, there was no Gloeo. We’re probably seeing it now due to the high temperatures of the past couple of decades—they’re favoring the Gloeo. They might have always been present on the sediments, but they just weren’t growing enough to be in the water column.”

Of the lakes Pratt tested, Moose Pond had the most visible bloom, with the maximum growth occurring in early August, when the water was the warmest. The testing site was in the middle basin near Lakeside Condominiums. Amy Tragert, who conducted a dock-to-dock informational tour on Moose Pond, also saw Gloeo in other locations. Pratt explained that Moose Pond is so clean and clear that it’s probably helping fuel Gloeo’s growth because it’s able to take advantage of plenty of sunlight. “I feel like if the bloom was really, really bad it might look like pollen scum,” says Pratt, “But I never saw it to the degree where it formed a scum.”

Though Moose Pond had the highest concentration of the lakes tested in this region, region, it was not a huge amount compared to lakes in New England and around the world. Gloeo is difficult to see unless you are actually looking for it. Consequently, it doesn’t get a lot of media attention, so if you haven’t heard of it before, you aren’t alone.

The big question is what to do about it. Similar to other algal blooms, it all boils down to reducing erosion and phosphorus flowing into the pond. To learn more about the top ten ways to protect lakes, visit the LEA Web site at www.mainelakes.org.